A Tribute to Dr. Berke, zt"l

Good morning, everyone. Today I want to share more about Dr. Joseph Berke zt”l. When I began writing about him in my previous post, I didn’t realize that he’d recently passed. “He is a frum Yid today,” I typed in unsuspectingly, and then went to Google to do a search for his picture. The results came up with a sobering blow. I saw the end date of his life: January 2021. My first thought was Covid. It turns out to be heart failure, but either way, it saddens me. I never knew him personally, but I did reach out through email, and he was very generous in responding back. I could have met him in Israel in 2019. We were both there at the same time. But I would have had to pay for a therapy session, and I let my pride and frugality get in the way. Boy, do I regret that now! He’s gone, I will never, ever meet him!

After that unfortunate discovery, I read a moving obituary written by his personal friend. It made me admire him all the more. So now I want to write my own tribute, but because I only knew him through his writings, it’s a tribute from a distance.

As I said before, Dr. Berke’s mentor R.D. Laing rejected the concepts of schizophrenia and mental illness. He said that mental patients are usually the smartest and most sensitive members of their families who are responding to some negative dynamic affecting everybody. If the family can label that one individual’s maladjustment with as “mental illness,” then they can say it’s the patient’s problem alone and go on believing there’s nothing wrong with them.

Dr. Berke put it slightly differently. In the book he co-wrote with Mary Barnes, he said that schizophrenia is not a disease, but a career. Launching on it requires a doctor, a patient, and one or more family members to persuade and/or coerce the patient into it. In other words, it’s a power trip to repress the patient. The same power trip happens between doctors and patients as the “career” progresses. Witnessing it was what sent Dr. Berke to the U.K. to join Dr. Laing.

As a new doctor at Columbia University Hospital (?), Dr. Berke was sitting in on a group therapy session being run by a more senior psychiatrist. A young woman had been brought in the night before. She was having what would be clinically described as a manic episode. She wouldn’t stop dancing, even when her downstairs neighbors complained about the noise. Her mother begged her to stop, but she wouldn’t. Then someone called the police, but since disturbing the peace isn’t enough to haul a person off to jail, they brought her to the hospital instead. A “rational” choice according to society’s rules, but not when you think it through. Just like overexuberant dancing isn’t a crime to be jailed for, it’s not a disease with a cure to be found in a hospital.

At the group therapy session that morning, the young woman began dancing up a storm all over again. The other patients liked seeing it, but the supervising doctor did not. He had his goals and agenda all prepared, and now she was disrupting the group. Like her mother, he tried telling her to stop, but she just kept going. That amused the other patients even more. Exasperated by the loss of control, the doctor called the orderlies to bring her to her room. Dr. Berke said they had to restrain her. It got much more violent than was warranted.

“This is not what I signed up for,” he thought. The senior doctor could have let the patients dance, but that meant letting them take the lead. The idea probably didn’t even cross his mind. He considered his goals for the session so sacrosanct that he saw fit to enforce them with the muscle of the orderlies. Is that therapeutic? Or humane? Should it even be considered “normal?”

So Dr. Berke left the U.S. and joined Dr. Laing’s healing community at Kingsley Hall where he famously aided Mary Barnes in her recovery. When Kingsley Hall closed down, he founded its successor community, the Arbours Center, which lasted for decades. So now I’ll skip over the decades, too, and talk about his 2015 book, The Hidden Freud.

As you see by the cover and subtitle, this book holds special interest to Jews. It explores Freud’s therapeutic relationship with the fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe - who knew? - as well as his conflicted attitude toward his own Jewishness. But while Freud was known for being anti-religion, the book makes the case that he had a hidden, softer attitude that showed through at times.

The book contains more history and theory than narrative, so it’s a much denser read than the Mary Barnes book. Parts of it were so theoretical, I just skimmed my way through. It’s too bad because Dr. Berke was demonstrating how Freud’s theories are a secular application of Kabbalah. I would have liked to see that explained more clearly in layman’s terms.

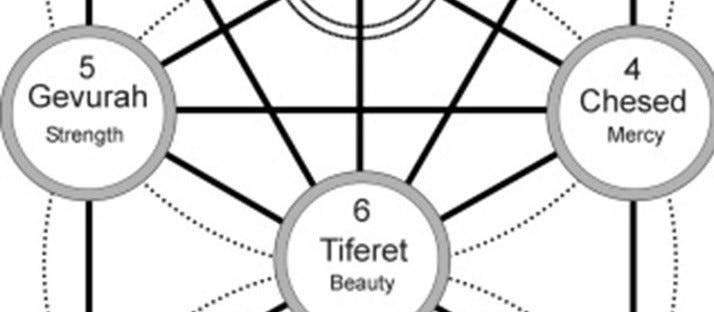

One of my emails to him included a question about that very overlap. My question was informed by the same ideas I shared in “The Kabbalah of Politics.” Here’s the diagram again:

As you may recall, chessed is kindness, but when taken to excess, it’s the abandonment of boundaries and sexual impropriety. Gevurah is restraint, but when taken to excess, it results in anger and violence. Tiferes is the combination of the two, but when they combine in the wrong balance, they become egotism. Therefore, I asked Dr. Berke, do these sefiros in their negative form correspond to id, ego, and superego? I’m still quite proud of that insight, but he never addressed it in his reply, and I was so grateful to be getting a reply at all, I didn’t push the point.

Because the book is so tough to get through, I’m linking some videos below as shortcuts. The first is the book launch held at the Freud Museum in London, which is at the site of his final home. It’s less than half an hour long. The other is a much longer lecture given at the David Cardozo Academy in Israel. Frum Jews with academic leanings will appreciate it.

When you learn the Torah of a departed scholar, he gets a merit in the World Beyond. And though not everything I’ve said here qualifies as Torah, may it all be a zchus for Dr. Berke zt”l.