The Kabbalah of Politics

Wow. My post on trans rights got over 300 hits on its very first day, which makes it my most popular article so far. Since it’s a hot-button issue, I imagine it will hold that record for a long time. Rather than try to top it, I want to address a response I received to a line in my version of “My Favorite Things.” That line is: Keeping the Torah while staying left-wing.

“How is that even possible?” someone asked.

It’s not the first time I’ve gotten some form of that question. To an outsider, liberal politics and Torah observance seem like an irreconcilable contradiction. But since I didn’t become Orthodox until my early twenties, I’ve always retained the liberal values I learned from my parents, as well as the anti-racism I developed from attending diverse public schools. When I began spending my time in Orthodox circles, finding like-minded Democrats became increasingly rare, but because I was committed to keeping a Torah lifestyle, I tried to square the circle. As a result, I’ve developed a political philosophy that can be shared in one compound sentence. Live a conservative life personally and have a liberal attitude toward others. But to fully explain this credo, I must refer to nothing less than the Jewish mystical tradition, the Kabbalah.

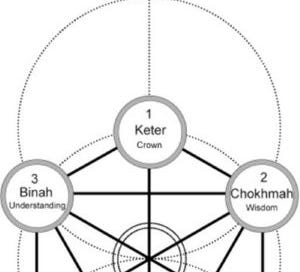

This famous diagram, sometimes called “the Tree of Life,” represents how pure spirituality – in other words, G-d – descends to reach humanity in the physical world. G-d is on top, represented by the crown, and we, along with the rest of this earthly creation, are the kingdom on the bottom. The holiness from on high filters through the eight spiritual qualities in the middle. In Hebrew, these qualities are called the Sefiros. The sixteenth century Kabbalist Rabbi Moshe Cordovero likened them to pieces of a stained-glass window.1 The blue pieces will look different than the yellow pieces when sunlight comes through them, but the same source of light shines through both.

Notice the triangles connecting the Sefiros. That represents the ways they combine with each other. So instead of a two-dimensional stained-glass window, think of the prism effect. Spirituality reveals itself in multi-faceted combinations.

The triangle I want to focus on is the one right in the center, formed by Sefiros Four, Five, and Six. Sefira Four is chessed. The diagram translates it as mercy, but other fitting synonyms are kindness, openness, and giving. Sefira Five is gevurah, translated here as strength, but I’d say “restraint” is more like it. Gevurah is the opposite of chessed, and restraint is the opposite of giving. Another way to think of them is as the dichotomy between love and discipline. As every good parent knows, you need a balance of both.

That brings me to Sefira Six, the merging point of the triangle. In Taoism, opposites yin and yang combine into a unified circle. Judaism is similar. The opposites combine into a third thing altogether, like a mother and father having a child. That’s why the diagram is made of triangles upon triangles.

The combination of kindness and restraint is tiferes. This diagram uses the word beauty, but other translations say “balance,” “center,” and “truth.” As Keats said, “Beauty is truth, and truth beauty.”

Every human soul contains these traits, but in different proportions. Some people are exceptionally kind and open-hearted. If you’re lucky enough to have a few people like that in your life, consider yourself blessed. But you might know other people who are much more restrained. That doesn’t necessarily make them mean or cold. They’re just not forthcoming. But beneath that calm exterior might lurk tremendous self-discipline. That’s why the diagram translates gevurah as strength. If you can restrain yourself under trying circumstances, you’ve got strength of character.

Of course, it’s possible to take these traits to such an extreme that they become negative. We’ve all heard of people who are “generous to a fault” or co-dependent. This is a step beyond that. This is the sort of giving that is so indiscriminate, it becomes inappropriate. It can even lead to sexual impropriety. When the Torah uses the word chessed in a negative sense, it’s in the context of forbidden relations.2 Without restraint, a naturally open and giving person can lose all sense of boundaries.

The reverse is true with a restrained, self-disciplined person. Without a kindly attitude, they’re likely to lose patience with everyone else for being so weak-willed. Perhaps you had a teacher like that. “What’s the matter with you? Can’t you control yourself? Get out of my classroom!”

When I first learned these concepts in She’arim College for Women, Rebbetzin Pavlov concluded her lesson with what became one of the defining insights of my life.

“People are supposed to be kind toward others and strict toward themselves. The trouble is, most of the time, they do the very opposite.”

I’ve reflected on that teaching many times over the years, and somewhere along the way, it melded with my views on politics.

Liberalism is kindness. Liberals want generous spending on the social safety net to make sure everyone is fed, healthy, and educated. But critics say we’ve taken openness to such an extreme, we’ve paved the way for promiscuity.

Conservatism is restraint. Conservatives want law and order, and they want to hold the liberals back from all their spending, which they view as irresponsible. Unfortunately, they’ve taken it to the extreme and become overly harsh, with militarism and mass incarceration as prime examples.

The answer, of course, is balance. Take what’s good from each side and use it to counterbalance the negatives. Thus, I’ve transposed my Rebbetzin’s teaching – be kind toward others and strict toward yourself – into my one-sentence political philosophy – live a conservative life personally and have a liberal attitude toward others.

That is how I square the circle. I choose to live a modest, even chaste life, but I don’t impose my standards on anyone else. Being conservative on personal matters doesn’t mean I accept conservative politics.

When I learned that kindness taken to the extreme could lead to sexual impropriety, I understood it perfectly. Having gone through my own hippie wannabe phase, I know how badly my openness messed me up. I welcomed the restrictions of traditional Judaism. It taught me some much-needed self-discipline.

I also had no trouble understanding why restraint taken to the extreme would result in anger and harshness. Any observation of human beings will show you that. But what I could not get my mind around, and what would puzzle me for years to come, was something I heard from my Hebrew tutor. She said that when tiferes is taken to its extreme, it becomes self-centeredness. That seemed more like a polar opposite than an abused extreme.

I actually stopped the class to get that question answered, and wasn’t satisfied with anything I heard, but eventually, I came up with my own answer. Balance, by definition, can have no extreme. There is only balance or imbalance, just there is only truth or falsehood. There either is a center, or there isn’t one. So since tiferes is a combination of two things, imbalance must be what results when you combine them incorrectly. In other words, whether you show yourself excessive kindness and go the path of “eat, drink, and be merry,” or you show excessive harshness toward others and just “look out for Number One,” you’re exercising selfishness.

All of recent American history can be viewed as a pendulum swinging between the extremes. The 1960’s were a time of generosity with the Great Society and civil rights legislation. On the negative side, there was plenty of sexual impropriety. Then came the conservative backlash with Nixon, which really settled in with Reagan, who, in his demeanor anyway, lacked Nixon’s unpalatable harshness. The AIDS crisis put an end to the sexual revolution, and of course there was Nancy Reagan’s message to us youth of the time: Just Say No. But there was one area where restraint was lifted – the de-regulation of the financial industry. Now people could be ungenerous and angry at “welfare queens,” while pursuing unbridled self-interest as though it would somehow be good for society. We saw in 2008 how well that worked out.

The pendulum swung back to the center with Obama’s election. His even-tempered character bespeaks the balance of tiferes. Unfortunately, the backlash to him was Trump, who represents the perversion of tiferes. Instead of truth, there were lies. Instead of beauty, there was glitz. And what could be more self-centered than plastering your name all over the world in gigantic gold letters?

An Orthodox friend of mine told me he was offended to the point of being shocked that I would apply the lofty Sefiros to lowly politics. If you agree with him, then ignore the politics, and focus on Rebbetzin Pavlov’s message: be kind toward others and strict with yourself. Or, as stated by Rabbi Yisroel Salanter: “A pious Jew is not someone who worries about his fellow man’s soul and his own stomach; a pious Jew worries about his own soul and his fellow’s stomach.”3 It’s a big enough job to maintain our own relationship with G-d.

And if you happen to be an atheist reading this, I hope you’ll see the wisdom in these teachings regardless of the source. As long as we work on loving each other and disciplining ourselves, perhaps this world can get into balance.

Pardes Rimonim 4:4, 17d-18a

Vayikra 20:17

From a list of Rav Salanter’s epigrams in Tenu’as haMussar, vol. 1 by Rabbi Dov Katz